The details: L.S. Dugdale, The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom (New York: Harper One, 2020).

The problem and the question: More and more North Americans have been dying poorly. We pursue a seemingly endless array of medical treatments with the hope of a cure, and, in exchange, often sacrifice our quality of life. We are dying alone and with regrets. And we die in fear, untethered from a sense of a bigger purpose. How can we support others’ dying and prepare for our own dying so that death is done “well”?

The thesis: To die well, we must live well.

What this means for Dugdale: Dying well means living with a sense of our finitude. We’re all going to die someday, and it’s best if we deal with that fact while we aren’t facing death head-on. That does not mean we look forward to dying, but that we have judged and arranged our todays (and tomorrows) with an awareness that we cannot do/have it all. We cannot be cured of death.

Dying well requires a connection to community and loved ones. Which is to say that we must be present for others when they are dying (to both support them and to be reminded of our own mortality), and we must be prepared to unashamedly invite others in to our dying processes. Community helps us answer – or, at least admit that we often have – lingering questions about our existence.

Dying well means considering our literal deathbed. The art of dying well is to curate, if you are able, your final days and moments so that you are at “home.” A hospital can be a “home” for various reasons, but Dugdale argues that hospitals often present barriers to dying well. So, thinking through what is important to you is a first step to dying in the bed and company of your heart’s desire.

Dying well requires that we acknowledge our fear of death. It is out of fear of death that we “wage war” on the illnesses that ravage our bodies. This fear is sometimes mistaken for a “desire to live,” though the quality of life one lives when on a third or fourth experimental drug says otherwise. It is natural to be afraid of what we do not know and what we cannot control, but Dugdale writes,“[N]ot all fear compels a person to submit to torturous procedures that are unlikely to help.”*. To die well while afraid is to “walk courageously…toward the terror and sadness.”** To stare back at the fear of death is the only way to die well.

Dying well means attending to the body and the spirit. Dugdale writes of “vandalized shalom,” where bodies, communities, and the world are not as they are meant to be and are affected by decay.*** Yet it is within (broken) community that we find meaning and transformation. And it is within communities of faith, Dugdale suggests, that we find spiritual grounding to ease despair and emptiness.

Finally, dying well entails devoting time—more than one might think—to the rituals surrounding death. While our culture around death has shifted significantly in the recent past, passing on to “professionals” the actions associated with saying our final good byes, Dugdale suggests that what is gained with efficiency does not offset what is lost ritually. Rituals, like preparing the body for burial or funerals, aren’t meant to be efficient, but to be effective markers of significant transition. In the case of death, they are meant to allow us to show love to the deceased, to the bereaved, and to contemplate our own mortality. What would it look like for families and communities to return to holding these rituals, rather than funeral homes? Would it help the living to live (and die) better and to mourn more fully?

Personal reflection: I finished this book on my birthday, a purposeful move…for though birthdays invite us to celebrate our lives and existence, with each passing year, they also mark, if we pay attention, our certain mortality. While I had a blip in my mid-20s where the idea of death filled me with utter sadness, I have largely felt unintimidated by death. I’m certainly not personally eager for it, nor do I wish anyone else an untimely death, but, with Dugdale, I have felt convicted that how we live (not what we have or ultimately what we accomplish) is how we die. And so I have tried to shape my life around priorities, which include faith, community, and no small amount of not-putting-up-with-crap.

Reading The Lost Art of Dying couldn’t have come at a better time–in the midst of a pandemic, in the midst of societal upheaval, and in the midst of the earth rebelling against human abuse. Each of these circumstances reminds us of just how interconnected we all are. How your ability to live well relies on my ability to live well. How your ability to die well — without fear, surrounded by loved ones at home — is intricately connected with my ability to die well.

It may seem strange to educate ourselves on dying well, while death feels far off, but as Dugdale suggests, what better time is there? What does it mean for you to live well? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

On a lighter but connected note:

*Dugdale, 98.

**Dugdale, 110.

***Dugdale, 150.

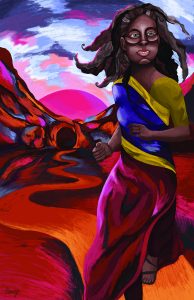

Your strength is good. Your strength will be intimidating. And the range of responses to it will be varied. Some will be caught by your assertiveness and want to dampen it. Don’t be surprised when others, including other (and usually, older) women, fear your strength and try to reassert the patriarchy. (These women are often blind to how they’re perpetuating patriarchy, pandering to the men they think they’ve got to keep happy.) Some folks, with whom you’ve established some level of trust, will acknowledge openly how your strength impacts them. They’re the ones who love you enough to see that your strength is a gift, even when they sometimes feel threatened by it. Love them and be gentle with them. (They’re human, too.)

Your strength is good. Your strength will be intimidating. And the range of responses to it will be varied. Some will be caught by your assertiveness and want to dampen it. Don’t be surprised when others, including other (and usually, older) women, fear your strength and try to reassert the patriarchy. (These women are often blind to how they’re perpetuating patriarchy, pandering to the men they think they’ve got to keep happy.) Some folks, with whom you’ve established some level of trust, will acknowledge openly how your strength impacts them. They’re the ones who love you enough to see that your strength is a gift, even when they sometimes feel threatened by it. Love them and be gentle with them. (They’re human, too.)