This is my sermon from 12.20.20, based on the text from Luke 1:26-38. I used the Inclusive Bible translation, which does not reference Mary as a virgin but a “young woman.”

You may have noticed that the translation of today’s Gospel reading chooses different language than what our ears might have expected. The Inclusive Bible purposefully refers to Mary simply as a “young woman.” Maybe you didn’t notice the changed language — or maybe you did, but have long since resigned to downplaying or ignoring the traditional reading. I’ve been there.

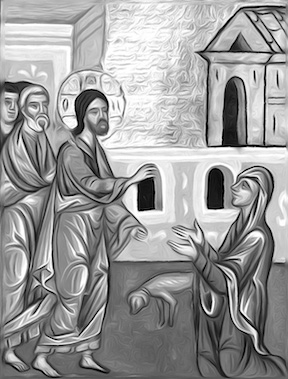

We are used to hearing here in Luke 1 that Mary is explicitly a virgin. That her sexual history matters. Not just that, but that her knowledge and experience of sex matters in the incarnation of God. If we read this text at all, we cannot help but stumble through the seeming emphasis on Mary’s virginity. And it’s impossible to escape in the Advent and Christmas season generally, with regular references in our favorite carols and art.

So, why would the translators of the Inclusive Bible purposefully choose a more vague term, “young woman”? The short answer is: because it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if Mary is, by clinical definition, a virgin or not.

Which of course, flies in the face of 2000 years of dominant Christian thought and theology that argues otherwise.

At the risk of condensing 2000 years of history that says it does matter, I’m going to sum up very briefly why I think the translators made this critical shift.

This text has been interpreted in a way that has impacted Western social structures, gender identity and formations, and concepts of sexual purity, particularly for women. Mary’s virginity has been used to instill a purity standard and the consequential body shaming and promotion of sex as a dirty act, again particularly for women.

In the face of two millennia of distorted interpretations, one has to change the language to make a point. I think the translators made the shift because the focus of this story isn’t meant to be Mary’s sexuality or sexual history. The focus of Luke 1:26-38 is the miracle of God affirming the human form to the extent that God chooses to inhabit it.

This aligns with God’s story as a whole: creation being inherently good and worth loving completely.

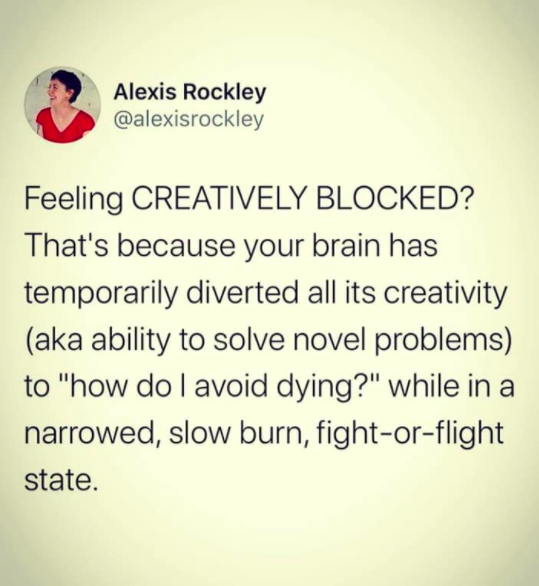

The credibility of the Good News does not rest on Mary being a virgin or not. So, this scripture falls in the category of needing some proactive interpretive remediation. We can’t just bypass it as a text that doesn’t matter when it has impacted our way of being for so long. Part of our burden and divine call is to dismantle life-leaching interpretations and rebuild what really matters.

That’s what we’re doing here today. I want to talk about two things that do matter in today’s text.

Mary Matters

First is that Mary matters! Her significance, or at least part of it, is that she is a discerner and doer of God’s dream. In the company of many of her Jewish ancestors, Mary is surprised by Gabriel’s visit and announcement of her role in God’s story. Luke says she is confused, perplexed. Even resistant.

This is a familiar pattern in the story of Israel – Abraham and Sarah were confused and perplexed by God’s promise of a son, even in their old age. The prophets were known to be true prophets only if they had resisted their call a bit.

Even Zechariah, earlier in Luke 1, is also visited by a messenger from God who announces the future birth of Zechariah’s son, John the Baptist. If you remember that story, Zechariah is incredulous, for Elizabeth, his wife, is also too old to bear a child. Zechariah, in his surprise, is rendered mute until John is born.

Mary follows in this very long tradition of being drawn into God’s story in a particular and compelling way. After the requisite wrestling with strange, good news, Mary, like her ancestors, carries on with life as though she believes the word of God given to her.

Mary’s body is undeniably significant in this story as the one who lovingly carries the child within her and delivers him. But more significant is her willingness to wrestle with the blessing of God, even as she does not understand it. More significant is Mary’s willingness to actively consent to participate in God’s dream.

We know this is Luke’s intent for Mary’s place within the story. Later, in chapter 11, as Jesus is in full-time ministry mode, a woman in a crowd cries out, “Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts that nursed you!” To which Jesus replies, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it.” [11:27-28.] Which is precisely what Mary did.

In Luke 1 and beyond, Mary steps into her vocation as a model disciple—one who discerns God’s word and does it, utilizing her body in faithful acts of discipleship. Her response to God’s invitation is Luke 1 is evident in the Magnificat. Her response is joyful consent.

Does this resonate with you? When have you been surprised by an invitation to participate in something greater than yourself?

God Affirms Human Form

The second thing that matters about today’s text is that God affirms the human form as good, beloved, holy: a sacred space worth inhabiting.

This is the message behind the text. As Dr. Kyle Roberts writes in A Complicated Pregnancy, “God did not avoid our body, our genetics, our brain, our human condition.”* God is not indifferent, aloof, apathetic to the human experience. God chose incarnation, to become mortal with all that that entailed. And God chose a natural, pleasurable process by which to enter the world.

I wonder if that was part of Mary’s surprise as well—that God would affirm our cells and our experience. That God would choose an ordinary body—her ordinary body—to bring Love to life.

But why should we be surprised? Again, God has said from the very beginning that our bodies and all creation are very good. It is we who have cast doubt on that truth. It is we who have believed lies that we should be ashamed of our ordinary bodies.

This is part of why a virgin birth does not matter: “a virgin birth gives us a different Christ than the one we really need.”** We need a Christ who knows pain and joy, pleasure and heartbreak, hope and despair. God said, “Yes,” to humanity, to the goodness of our bodies. God chose the human form because God loves the human form.

What matters in this story is that Love chose to become human, offering the ultimate affirmation of our full, embodied belovedness.

An Invitation to Love Our Bodies

One of the invitations of today’s scripture is to allow ourselves to be surprised that the human body is beloved and necessary in bringing God’s Love to life.

Body positivity is a bit of a buzzword these days. Lizzo, an amazing singer and rapper, has been a vocal advocate for body love the last few years. In particular her song, “Juice,” is what one commentator calls an “anthem” of self-love and respect. She centers the goodness of her body in the song, a profoundly prophetic message as a Black woman. While that might initially sound individualistic, Lizzo claims her liberation and expresses her joy in a way that echoes Mary’s song. Mary’s song points to a deeply personal, internalized sense of worth and goodness, that then flows out beyond her self.

“My body can do this. My body is worthy of birthing the Holy One.”

Like Lizzo proclaims, Mary, too, is profoundly empowered and participating fully in the incarnation of Love. The incarnation that needs Mary’s body, individually first – all of our bodies, collectively – to bring Love to life.

An Invitation to Love Others’ Bodies

The roll-on effect of this is that we are reminded that all human bodies are beloved and necessary in realizing God’s shalom – including those bodies we might consider enemies.

I want to share with you a poem by U.S. poet Jane Kenyon called “Mosaic of the Nativity: Serbia, Winter 1993”. Yugoslavia was in the midst of violently breaking up in the winter of 1993. As wars often are, it was a complex conflict fueled by religious tensions. On Orthodox Christmas Day, in January 1993, Bosnian forces launched a surprise attack on the Serbs, knowing that Serbian Orthodox Christians would be unprepared on this very special, holy day. This is what Kenyon is referencing in her poem.

On the domed ceiling God

is thinking:

I made them my joy,

and everything else I created

I made to bless them.

But see what they do!

I know their hearts and arguments:

“We’re descended from

Cain. Evil is nothing new,

so what does it matter now

if we shell the infirmary,

and the well where the fearful

and rash alike must

come for water?”

God thinks Mary into being.

Suspended at the apogee

of the golden dome,

she curls in a brown pod,

and inside her the mind

of Christ, cloaked in blood,

lodges and begins to grow.

“What does it matter now?” It matters that God loved the world so much that God took on human form. It matters that God took on human form, affirming “our bodies, our genetics, our brain, our human condition.” It matters that God chose Mary, an ordinary young woman, to lead us with her example of bold discernment and action. This is what matters. This is Good News.

Before Gabriel departs from Mary, they offer a blessing; so I offer this Advent blessing for you:

The Holy Spirit will gently rest on you,

a delicious glow that grows

from the tips of your toes and fingers

to the top of your head.

The Most High will empower you

and energize you

and the Love you bring to Life

will free us all.

I pray it be so.

*Kyle Roberts, A Complicated Pregnancy: Whether Mary Was a Virgin and Why It Matters (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017), 179.

**Roberts, 183.