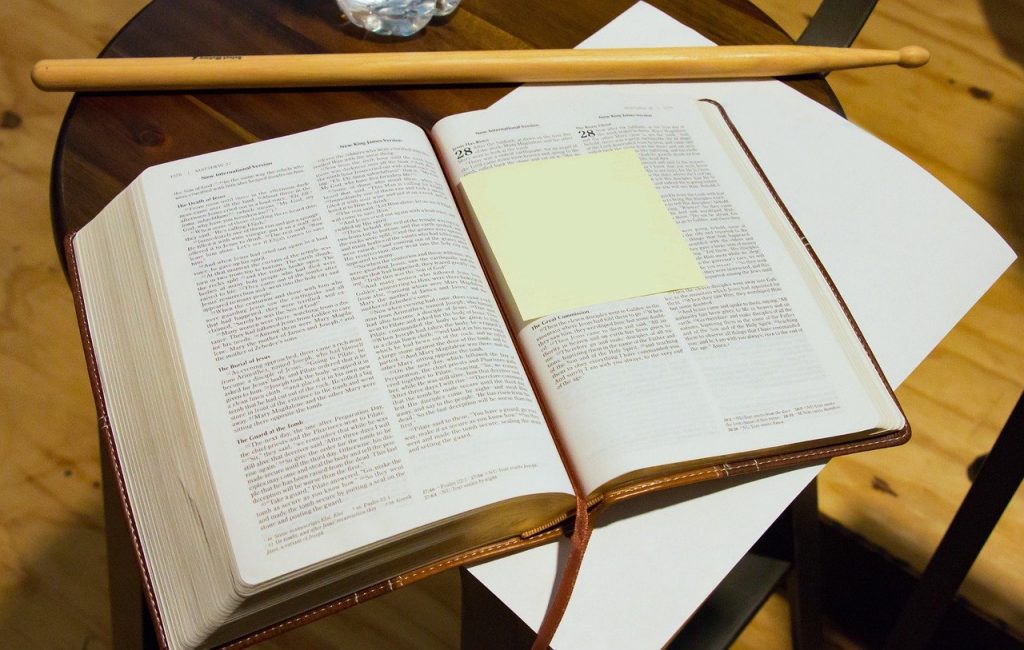

The manuscript my sermon from 12/18/22 at Madison Mennonite was based on. The scripture readings for the day were John 1:1-5 and Psalm 126.

As may be evidenced by now, Justin and I have chosen to make a household without the permanent presence of human children. Perhaps that’s a choice we’ll talk about more fully at some point. But knowing this, and in her own wisdom and desire, my sister invited me to the births of her twin daughters, who are soon to turn 10. Though I’ve been present for other animal births, witnessing the birth of Sylvia and Cora was a singular experience in my life.

There in the hospital delivery room, after being induced and waiting and waiting for contractions to come…there finally came a point, several hours in, when the inevitability of birthing these two set in—when there was no biological choice but to push, guided through the process by Frances, the midwife.

And eventually, out they came: first Sylvia, or “Baby A” as she was known at the time, then Cora, “Baby B.” My mother, also present, was the first to hold Sylvia. I was the first to hold Cora, as my brother-in-law stayed by my sister, who rested for a bit before pushing out the placenta.

Hearing again the prologue from John 1 this season, and letting the midwife’s perspective filter into the text, I think of that delivery room that cold winter’s night, ten years ago. I think about the long, long wait of bringing an essence, a dream into a warm, pudgy, fleshy form.

In the beginning, many moons ago, this hope, this Original Love, was formless and void, mingling with a sacred watery chaos.

After the beginning, but before labor really kicked in, it took time, perhaps millions of cycles of cosmic heating and cooling, of contractions and deep breathing, until the inevitable need to push arose, and the Word was coaxed and coached into a form you and I would recognize. A form that could be held and swaddled. A form that was called “Word” for a little while, until slowly we began to know them as “Jesus.”

It would have required serious preparation, I imagine, this long gestation, punctuated by pain, the cosmos gasping for breath. Layered under John’s words, there is a Divine Struggle to bring an idea to birth, an effort to make real what was hoped for. A struggle willingly made by a mothering God. Without a doubt, there was in the beginning, a struggle, and the struggle was real. The struggle is still real.

Perhaps this phrase is a bit jarring in this moment… “The struggle is real” for many of us conjures up images like those that circulate on social media: one of my favorites — someone with a hair dryer in one hand and an iron with the bottom facing up in the other hand, a piece of pizza being reheated using the two devices… The struggle is real. “The struggle is real” is a phrase that encapsulates the ironic frustration of rather mundane inconveniences.

But the history of the sentiment tells another story.

“The struggle is real begins in hip-hop culture, where the struggle refers to the oppression… faced by black Americans… Use of this struggle dates to the” 1980 and 90s, “but it was likely influential rapper 2pac who popularized the phrase the struggle is real on his 2002 posthumous track, “Fame”. “(https://www.dictionary.com/e/slang/the-struggle-is-real/)

We are reminded that “the struggle” has disparate meanings for folx in our communities.

What Tupac names, and other persons of dominated groups have attested to, is that an imposed struggle can be a form of oppression. Racism, poverty, climate change, homelessness, transphobia—these obstacles that dehumanize or that strip the dignity of humans or of the earth are to, without a doubt, be resisted by all of us.

At the same time, we live in a society where the dominant culture tends to suggest that pain and struggle are unnecessary—problematic even. The ideal life is one without pain—at least pain that “I” don’t have to feel. This can be made possible, in large part, by outsourcing one’s hurt. In the process, though, one’s capacity for growth is stunted.

My hunch is that we’ve each experienced this in our own lives: times when we have wanted to avoid pain and so passed it onto others; or when others have done that to us. And of course, it is systemic in our society, too, a central tenet of patriarchal white supremacy.

This is what some call “dirty pain.” Resmaa Menakem, author of My Grandmother’s Hands, writes, “Dirty pain is the pain of avoidance, blame, and denial. When people respond from their most wounded parts, become cruel or violent, or physically or emotionally run away, they experience dirty pain.” It’s pain that gets stuck in the body and inhibits growth. It’s the kind that is transferred onto others, particularly those who are more vulnerable.

And, there is clean pain. Clean pain is the pain that mends and can build your capacity for growth and resilience. “It is the pain we experience when we don’t know what to do, when we are scared, and when we step forward into the unknown anyway, with honesty and vulnerability.” (Menakem)

Clean pain, though still painful, is natural. It’s grief we feel in transitions. It’s the soul-stretching sensation of being called out by a trusted friend. It’s the disappointment of failure, or the death of a dream. It’s the pain we experienced the minute our bodies left the womb and we felt the physical shock of emerging into bright light and cool air, so unlike our placentas.

As much as I hate to admit it, it seems like we actually need this kind of struggle in order to grow. This kind of struggle makes us more human, more compassionate, more loving, more just.

bell hooks, in a dialogue with Cornel West, spoke about the tension that we feel around letting clean pain be a part of our stories, of letting struggle shape us, “We also need to remember that there is a joy in struggle. Recently, I was speaking on a panel at a conference with another black woman from a privileged background. She mocked the notion of struggle. When she expressed, “I’m just tired of hearing about the importance of struggle; it doesn’t interest me,” the audience clapped. She saw struggle solely in negative terms, a perspective which led me to question whether she had ever taken part in any organized resistance movement. For if you have, you know there is joy in struggle…” (Hooks, Yearning, 1990)

hooks names something so vital for our experience of struggle, of pain—whether clean pain, dirty pain, or a mix of the two. And that is: the role of the community is to witness the struggle, to midwife one another through the contractions and labored breathing. The point is not to fix or erase the pain, but to validate the hurt, to offer an alternative perspective, and to help us keep pushing or resting—whatever our bodies are telling us we need.

In this last week before Christmas, as we cross over the solstice, we move through a holy time of transition, where the darkness, if we choose to enter it, can be a fertile, sacred space with potential for joy and growth. The midwife’s stanza for this week reminds us that to allow the Divine to be birthed in us is a sacrifice, as we offer our bodies to be broken open, like the ground receiving a seed. So, too, the psalmist sings of the tension of knowing God’s love and nurture, and yet struggling to make sense of the pain of exile and disorientation. There is a longing in Psalm 126 to make sense of the struggle, and to come out the other side knowing transformation.

These sacrifices—sacred struggle—make possible the birth of justice, of a love most profound, of the possibility of a solidarity that frees us, too. Like the wise MMC women shared two weeks ago, birthing work is messy work, what with the sweat and blood and urine and tears and all other kinds of bodily fluids.

Preparing the way to bring our dreams, our ideas, justice to life is work and at times it is incredibly painful. It takes time, perhaps millions of cycles of our souls heating and cooling, our bodies pushing and sweating, for the Word to be coaxed and coached into existence.

As we go this week,

may we find safe places to be broken open

may we be safe places for others who are in pain

may we find courage to enter into the struggles that we face:

in our bodies, in our relationships, in our grief, in our struggle to care

may we know that we are struggling together,

in solidarity and in hope that the Child of Peace—

the Infant of Justice—

is being born in us once more.

I pray it be so.