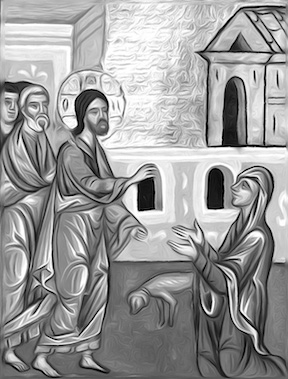

Background: A few years ago, I reflected on the Parable of the Sower in Matthew 13:1-9. This sermon, shared at Madison Mennonite on 7/12 and Germantown Mennonite on 7/19, “grows” out of those initial thoughts, expands them, and builds in the other Revised Common Lectionary texts of the day, Psalm 65 and Isaiah 55:10-13.

God the Good Gardener

Scripture is laden with metaphorical imagery for God and the way God acts in Creation. Throughout both the Old and New testaments we encounter God in many forms – God is like a rock, a refuge. God is like a warrior, a sovereign, a potter. God is our metaphorical father and mother. God is like an eagle, a mother hen. God is a midwife, a bakerwoman. And so on…

As we hear in our scriptures today, God is like a gardener. Psalm 65, which we heard in the call to worship, declares that God “visits the earth and waters it.” In the Parable of the Sower, God scatters the Word on the ground that stretches out before God. And, in Isaiah 55, God waters the earth with God’s word, and the earth erupts with golden grain.

This image of God as a Gardener comes at a good point in our lives, here in the northern hemisphere, for seeds planted in earnest earlier in covid have taken root, and their abundance has begun to spill out and over trellises. As one MMCer put it, we are approaching the season where gardeners must face the formidable “Deluge of the Green Bean.”

It is in this context, then, that we hear the parable of the sower, making connections as gardeners ourselves or as those who enjoy the plentiful harvests of others’ farms and gardens.

Land acknowledgment

I consider myself an average gardener. Much of my knowledge about gardening is the result of experience passed down through my family. Yet, it’s important to acknowledge that the gardeners and farmers of my family have accumulated that knowledge primarily as settlers on the land of peoples systematically displaced by European conquest and occupation. So, I offer this adapted land acknowledgment today as I share my reflections, a tension I and white folks must hold as we seek transformation and as we interpret biblical texts on the land.

Questioning Easy Interpretations

The parable of the sower is familiar enough to most of us that we know, without even reaching the interpretation of the parable, where the story is headed. The suggested lectionary reading includes the parable’s interpretation, but I left it out on purpose…

If there’s anything gardeners know and can agree to, it is this: one must resist predictable explanations and expectations when it comes to seeds. In honoring that, I resist the traditional, flannelgraph-worthy punch line of this parable: that some people are good because they’re prepared for the Gospel and some people are bad because they squander the Gospel.

As a gardener, I want to resist that dualistic interpretation. I want to resist it because when I reflect where I am in this parable, I see evidence that I’ve got all of these circumstances in me: sure, the fertile soil…but also the thin, rocky soil, the hungry birds, and no shortage of thorns or weeds. I imagine this is true for most, if not all of us. Each of these has a purpose for us as we grow in our understanding of who we are as followers of Jesus.

Thin, rocky soil

When the sower sows seed into thin, rocky soil, is it really all for nothing? The seed sprouts, grows quickly, and then dies.

But might what is gained in the long run balance the short-term loss? In other words, while there will be no harvest of grain this year from that seed, all is not lost. The plant that does grow will return to the earth, amending the soil as it composts. Over time, perhaps with the help of rain and animal droppings, too, seeds flung into this rocky soil will do the slow work of building up the land, until one day, there is a noteworthy harvest.

The invitation of the thin, rocky soil is to recognize that the places within us where growth feels tenuous or unlikely, those places still hold profound potential. God the Sower takes the long-view of who we are becoming. And tosses seed where most other gardeners would leave the ground fallow.

Weeds

Then there are the weeds. While the source of this quote might be surprising, a character in Jim Thompson’s 1952 thriller, The Killer Inside Me, states something gardeners love to re-quote (without knowing the source). The quote is: “A weed is a plant out of place.’ I find a hollyhock in my cornfield, and it’s a weed. I find it in my yard, and it’s a flower.”

It seems to me that so-called weeds have their own purpose and worth – whether retaining the soil’s moisture or reducing erosion or simply being a native part of an ecosystem we don’t totally understand. What if the invitation is to take the weeds – plants neither good nor bad, just in the wrong place – and move them to where they won’t choke out the fruit of the Spirit?

Birds

Then there are those hovering, hungry birds. I can only imagine that if I were in the crowd when Jesus was mentioning the birds that come and steal the seeds, it would have occurred to me about 10 minutes after Jesus had already pushed the boat off into deeper waters…to remember that there was another time when Jesus said something about the birds, and how they neither sow nor reap, and yet their heavenly Creator provides for them.

Well, how do I know it’s not the same birds from that example that are coming and taking the seeds in my field? Is there not enough grace and love in these good news seeds to share with all God’s creation? The invitation here is to see that God takes into account that all creation relies on God’s generosity. In turn, we are invited to resist our hoarding compulsions and to move instead into a spirit of jubilee – not just for humans, but for the land and creatures, too.

Fertile Soil

Which leaves us with the fertile soil. One commentator on this text writes that the yield is “exceptional”; yet another says it’s “miraculous.” These seem like distinctly different descriptions – one is possible, and the other is only possible with God’s intervention. Both, I believe, are right.

Miraculously, God-the-sower imbues seeds with the most unexpected, unexplainable potential and possibility. That there is any of God’s word scattered in our lives is a gift. And exceptionally, we are created with the capacity to respond to God’s word — we do not rely on grace alone. We can reflect on what sort of spiritual life we are cultivating.

The invitation of the fertile soil is to celebrate the average and exceptional fruits that we bear. We are also invited to bask in the harvests borne of mystery and miracle.

The Sower Sticks Around

As much as the parable teaches us about us, it also teaches us about the nature of God…who, amongst other attributes, is like a good gardener. A good gardener sows seeds in a field and then continues to tend the field. God does not abandon God’s garden, but nurtures it through the seasons and years. Listen to these words from Isaiah 55:10-13 (NRSV).

10For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven,

and do not return there until they have watered the earth,

making it bring forth and sprout,

giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater,

11 so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth;

it shall not return to me empty,

but it shall accomplish that which I purpose,

and succeed in the thing for which I sent it.

12 For you shall go out in joy,

and be led back in peace;

the mountains and the hills before you

shall burst into song,

and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands.

13 Instead of the thorn shall come up the cypress;

instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle;

and it shall be to the Lord for a memorial,

for an everlasting sign that shall not be cut off.

God the Gardener does not sow seeds that sprout empty promises or empty threats. God the Gardener uses choice seeds, honest in their purpose, true to their description, and imbued with unimaginable potential. God the Gardener can create growth in spaces where the most seasoned farmer wouldn’t want to waste good seed.

Where God is the Gardener, the land is filled with jubilation, and the trees give a standing ovation. Where God is the gardener, ancient sequoias overshadow the thorns and trees of life crowd out the briers.

Where God is the gardener, the thin soil and the rich soil will be equally peppered with word-seeds of faith, hope, and love. Where God is the gardener, the birds and the field mice and prairie dogs will find there is enough for them, too. Where God is the gardener, plants once thoughtlessly type-cast as weeds will be transplanted into God’s front yard.

May we be gifted with ears to hear and eyes to see that as God sows God’s word, holiness and beauty are abundantly cultivated in us and all around us. May we give thanks to God–the good gardener, the best farmer–for lovingly and faithfully tending the fields of our souls in each and every season.