In the final month we lived in Virginia, alongside the requisite sorting, box-making, and packing, I finished a project that was nearly a decade in the making. The project hadn’t languished because it was particularly difficult or big—it was just one of those projects that lies fallow for awhile until it’s clear that its time has arrived.

The project was a small wall hanging—no more than 2’ x 2’. In early 2011, I had moved to Pittsburgh to begin a Master’s program, taking with me my sewing machine and a stash of fabric as my study-break hobby.

This was not just any fabric, though; it was fabric I had gleaned from my mother’s stash and from fabric she had gleaned from both of my grandmothers, who were both deceased. The fabric was mostly scraps—small bits leftover from yesteryear’s (or yesterdecade’s) projects, likely clothes and quilts. Some pieces were no bigger than a couple inches across. Most were wonky remnants. All had a bit of that musty, mothball grandmother’s-closet smell.

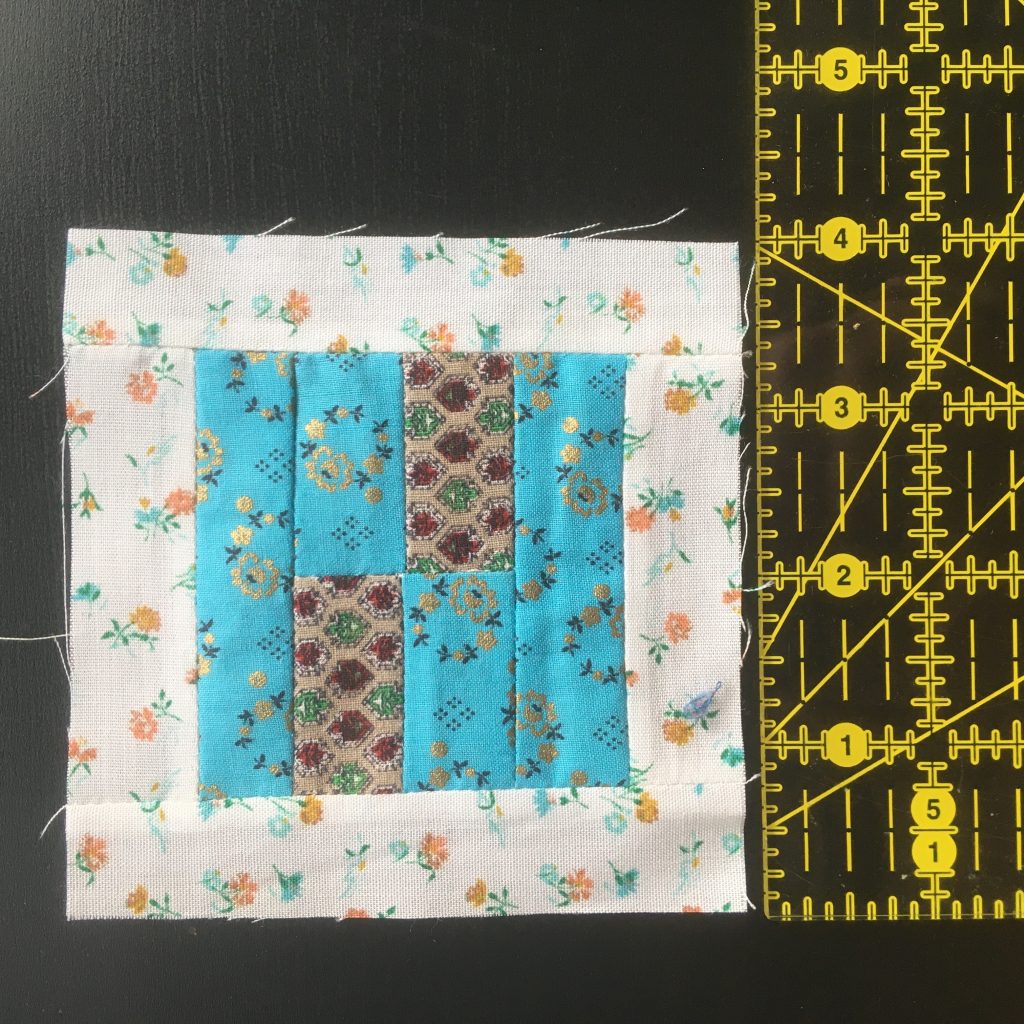

I began taking the scraps and piecing them together, using a technique called “crazy quilting,” where symmetry is not a goal, at least until you finish the square.

Eventually, I had made about 35 squares. Half of them, I pieced together and quilted for my sister. The other half sat in a box for the rest of our time in PA. And then it sat in a box in a basement while we lived in London. And then, still in the same box, it sat in my study while we were in VA.

Years later, at the start of 2019, I resolved to finish what I now called my “Grandmother Project,” to put the final squares together and make a wall hanging for myself.

By Summer 2019, it was still in the box. But as a move loomed in our future, I felt a poke of “quilter’s conscience.” And then, separately, when it seemed clear that my ordination for ministry would be happening before we moved, I felt the critical impetus for following through on my resolution.

I felt this because I linked the possibility of my ordination with my ancestors—particularly ancestral women with whom I shared either genes or spirit.

So, in August and September 2019, I finished piecing the top. I carefully layered the backing, batting, and top together. I then quilted it by hand. Finally, I bound the edges and it was complete. With the ordination service approaching, I requested that “Grandmother Project” be part of the worship visuals as a symbol of gratitude and interconnectedness to those who have “made a way” for my journey.

As I stood facing the congregation that morning, I also stood in front of my handiwork, my grandmothers’ and mother’s fabrics, and I was anointed for ministry. My mother and mother-in-law joined me, draping a vibrant stole around my neck that they had collectively made. It was a sacred intersection of blessings, of standing on hallowed ground with women who had paved the way for me, whether or not they knew it.

Recently, I’ve taken out more of these old scraps from my grandmothers, my own fabric occasionally mixed in. As I cut them into squares for some future project, I think of my grandmothers and I wonder about their lives.

As I’m currently reading My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Path to Mending our Bodies by Resmaa Menakem, at times I reflect on the mystery of my own grandmothers’ hands.

I think about the scars and trauma my ancestors endured, and wonder how much of that lingers in me. I wonder about how my grandmothers thought about race, gender, white privilege, or the land they inhabited. I smile at the question with an unknowable answer: What would they think of their granddaughter-pastor?

In the absence of answers, I keep cutting squares and asking for their blessing and wisdom. I offer my gratitude for them, for their labors in keeping loved ones clothed and warm with all varieties of colors and patterns. And I let their love shape my ministry, as I think now of those who will lead us in the years to come.